Clarifying the Amount of Protein in an Athlete’s Diet

Written By: Jennifer Broxterman, BScH Foods & Nutrition

Registered Dietitian & Sports Nutritionist

NutritionRx Website: www.nutritionrx.ca

Email: info@nutritionrx.ca

By far, the most commonly asked question I receive when counseling an athlete or delivering a nutrition talk is clarifying the “right” amount of protein an athlete should be eating in a day. Protein is critical to growth and development, including the growth and repair of muscle tissue, which has earned protein a special place in any athlete’s diet. However, its role can be overstated, and athletes often forget that no one particular nutrient by itself ensures a balanced diet that best fuels performance. What I often see in practice can only be described as a “protein obsession”, where daily protein intake and supplementation is such a fixation for a particular individual that diet quality suffers at the expense of optimal intake of calories (either too little or too much), carbohydrate, and/or fat.

So let’s start off with a short quiz1 to test your current knowledge of proteins. Read the following statements and decide if each is true or false. Answers will be provided at the end of this article.

- Skeletal muscle is the primary site for protein metabolism and is the tissue that regulates protein breakdown and synthesis throughout the body.

- In prolonged endurance exercise, approximately 3-5% of the total energy used is provided by amino acids.

- To increase skeletal muscle mass, the body must be in positive nitrogen balance, which requires an adequate amount of protein and energy (calories).

- The daily recommended protein intake for strength athletes is 2.0 to 3.0 grams per kilogram body weight, twice that recommended for endurance athletes.

- Strength athletes usually need protein supplements because it is difficult to obtain a sufficient amount of protein from food alone.

Recommended Protein Intake for Athletes & Non-Athletes

Numerous years of validated scientific research has led to well-established protein recommendations for non-athletes. For healthy adults, the Dietary Reference Intake (DRI) for protein is 0.8 g of protein/kg body weight/day2, which recommends a suggested amount of protein to eat each day (in grams) to maintain good health for the majority of the population. This number is based on two key assumptions: (1) energy (caloric) intake is adequate, and (2) the protein consumed is of high quality (high biological value). In Canada and other developed nations, protein quality and total daily protein intake is usually not a concern, especially in non-vegetarian individuals… but more about that later.

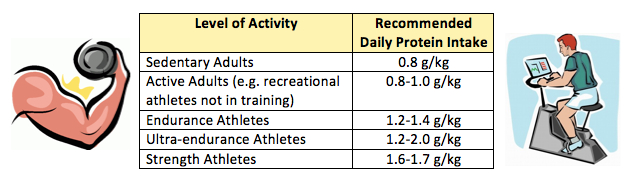

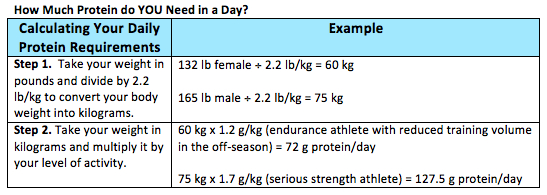

But what about athletes? There is a general consensus among the scientific community that strength, endurance, and ultra-endurance athletes require higher amounts of protein in their diet compared to their non-active counterparts, which is calculated based on the predominate type of training the athlete participates in. A good rule of thumb for an athlete’s ideal protein intake is somewhere in the range of 1.0-2.0 g of protein/kg body weight/day1, depending on the sport and point in the training cycle. Below is a table to help specify general protein recommendations based on activity.3

Protein in the Diet

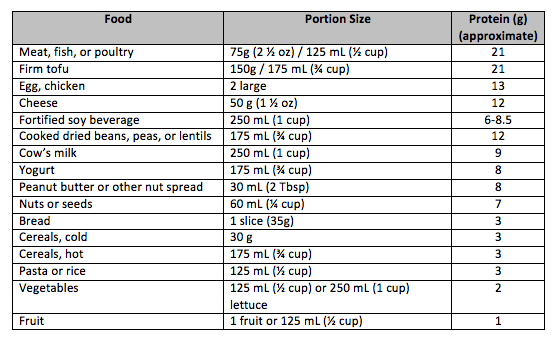

Protein is found in meats, fish, poultry, milk, eggs, cheese, yogurt, dried or canned peas, beans and lentils, nuts and seeds and their butters, and in soy products like tofu and soy beverage.4 Grains, fruits and vegetables also add small amounts of protein to your diet. Eating protein from a wide variety of food sources will help you meet your needs for nutrients like iron, zinc, vitamin B12, calcium and vitamin D.

Protein powders (e.g. whey powder) will add protein to your diet, but do not have significant sources of other nutrients that your body needs. In contrast, milk is a source of protein, but also has calcium, vitamins D, B12 and B2 (riboflavin).

To estimate the amount of protein in your diet, keep a food record for 1 or 2 days, recording what you eat and drink. Then add up the protein in your diet using the amounts in foods listed below:

–

Short-Term Effects of Too Much Protein

In the past, caution was warned against very high-protein diets (defined as a protein intake greater than 2.0 g/kg/day), especially for those athletes using protein supplements. It was thought that excessive protein intake would stress healthy kidneys and the liver in the short-term. In well-training athletes and bodybuilders with normal kidney function, no short-term harmful effects on kidney function were detected in one study that had athletes consume 2.8 g of protein/kg/day.5 However, large amounts of protein (>2.5 g/kg/day) from the diet and through supplementation can result in some potential training and performance problems, mainly dehydration, low carbohydrate stores, and excessive caloric intake causing weight gain.1

Large amounts of protein can cause dehydration because additional water is needed to metabolize protein. Urea, one of the by-products of protein metabolism, is an osmotically active compound that attracts water. Urea is excreted from the body via the kidneys and into the urine, resulting in a larger volume of urine and increased water loss from the body. Consuming large amounts of protein may also come at the expense of eating enough carbohydrates in the diet. After several days of following a high-protein, low-carbohydrate diet while exercising strenuously, muscle glycogen stores become quickly depleted, negatively impacting performance and recovery time. Finally, if protein intake consistently exceeds an athlete’s energy requirements, then caloric intake may be too high and body fat may increase over time.

Long-Term Effects of Too Much Protein

In the long-term, studies of athletes and non-athletes have shown that excessive amounts of protein in the diet can results in increased urinary calcium excretion.6,7 To neutralize the acid that is produced when protein is metabolized in the kidneys, the body draws calcium carbonate from the bones. The long-term effects of high-protein diets on bone metabolism and the potential for osteoporosis are still unclear at this time.6 There is also some medical evidence that lifelong high-protein consumption may affect the lifespan of the kidneys and accelerate the progression of renal disease.8

To make a long story short, too much of a good thing, even protein which is an important part of any athlete’s training diet, can become a bad thing over time. Moderation and balance with other macronutrients is key!

Answers to Protein Quiz:

- FALSE. Skeletal muscle is an important site for protein metabolism but the liver plays a primary role both in protein metabolism and its regulation.

- TRUE. Although carbohydrate and fat provide the majority of energy used in prolonged endurance exercise, when carbohydrate stores are low, energy is provided by amino acids. Research studies suggest that of the total energy used, 3-5% is derived from amino acids.

- TRUE. Energy and protein intake are closely related, and sufficient (but not excessive) amounts of both are needed to achieve positive nitrogen balance and skeletal muscle growth.

- FALSE. The daily recommended protein intake for strength athletes is typically 1.6 to 1.7 g/kg, slightly higher than the 1.2 to 1.4 g/kg recommended for endurance athletes.

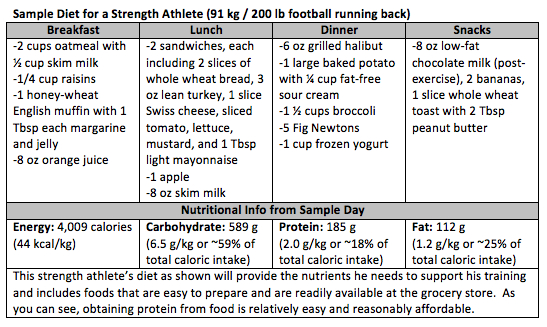

- FALSE. Obtaining sufficient protein from food alone is not difficult and surveys of athletes haven shown that many consume more than what is recommended. Protein supplements may be desirable for athletes for reasons such as convenience, but are optional and not necessary.

References:

1. Dunford, M. & Doyle, J.A. (2008). Chapter 5: Proteins, in: Nutrition for sport and exercise. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Cengage Learning.

2. Institute of Medicine (2002). Dietary Reference Intakes for energy, carbohydrate, fibre, fat, fatty acids, cholesterol, protein and amino acids. Food and Nutrition Board. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

3. American Dietetic Association, Dietitians of Canada, and the American College of Sports Medicine (2000). Position paper: Nutrition and athletic performance. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 100(12), 1543-1556.

4. PEN. Dietitians of Canada (2009). Quick Nutrition Check for Protein.

5. Poortmanns, J.R. & Dellalieux, O. (2002). Do regular high protein diets have potential health risks on kidney function in athletes? International Journal of Sports Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism, 10(1), 28-38.

6. Kerstetter, J.E., O’Brien, K.O. & Insogna, K.L. (2003). Dietary protein, calcium metabolism, and skeletal homeostasis revisited. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 78(3 Suppl), 584S-592S.

7. Heaney, R.P. (1993). Protein intake and the calcium economy. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 93(11), 1259-1260.

8. Lentine, K. & Wrone, E.M. (2004). New insights into protein intake and progression of renal disease. Current Opinion in Nephrology and Hypertension, 13(3), 333-336.

Wishing you health & happiness,

♡ Jen

Jennifer Broxterman, MSc, RD

Registered Dietitian

NutritionRx: happy, healthy living with our team of Registered Dietitians

Prosper Nutrition Coaching: a world-class nutrition coaching certification

+

+

+

Want to work with a NutritionRx Registered Dietitian?

Learn more here: Nutrition Packages & Rates

+

+

+

Want to become a Certified Nutrition Coach?

Learn more about our habits-based Prosper Nutrition Certification